[column]Learning outcomes

Level 2 case study: You will be able to:

- interpret relevant lab and clinical data

- identify monitoring and referral criteria

- explain treatment choices

- describe goals of therapy, including monitoring and the role of the pharmacist/clinician

- describe issues – counselling points, adverse drug reactions, drug interactions, complementary/alternative therapies and lifestyle advice.

Scenario

You are a hospital pharmacist visiting your regular general medical ward to review patients and provide pharmaceutical advice. Mr HA is a 50-year-old accountant who was admitted 2 days ago to hospital following a blackout whilst watching a football match with his son. His preliminary examination reveals bruising to his left arm and upper thigh for which he has been prescribed paracetamol 1 g four times daily and as required ibuprofen 400 mg three times a day.

His past medical history indicates that that he is on no medication and seemed to be a reasonably fit man for his age with no existing diagnosed medical conditions. On examination he is slightly overweight at 81 kg, he smokes 20 cigarettes per day and drinks approximately 30 units of alcohol per week. His blood pressure on admission was 165/80 mmHg with a heart rate of 90 beats per minute. This degree of raised blood pressure and heart rate has been maintained over the last 48 hours. He is subsequently diagnosed as having hypertension.

Questions

1 What is hypertension?

2 What are the appropriate treatment targets for this patient’s blood pressure?

3 Besides blood pressure, what other advice and treatment does this patient require to ensure his risk of a cardiovascular event is reduced? Give clear reasons for your advice and explain the risks associated with not taking this advice.

4 What are the main classes of drug used to treat hypertension?

5 Which class of drug would be appropriate first-line treatment for Mr HA? How would this treatment choice be affected if the patient had been of Afro-Caribbean origin?

6 For one of the classes of drugs mentioned in question 4 indicate the following:

- a drug from that class

- a suitable starting dose and frequency

- the maximum dose for hypertension

- three contraindications

- three common side-effects.

7 In view of Mr HA’s age he requires cardiovascular risk assessment. How would you assess this patient’s cardiovascular risks?

Answers

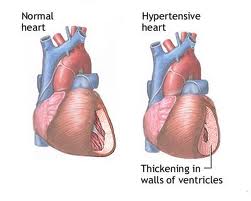

1 What is hypertension?

Hypertension (in people without diabetes) is defined as a sustained systolic blood pressure of (SBP) of ≥140 mmHg, or sustained diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of ≥90 mmHg (Clinical Knowledge Summaries, 2007).

Note: Hypertension is considered to be sustained if an initial raised blood pressure measurement persists at two or more subsequent consultations).

2 What are the appropriate treatment targets for this patient’s blood pressure?

The aim of treatment is to reduce blood pressure to 140/90 mmHg or below (NICE, 2006).

Note: Patients not achieving this target, or for whom further treatment is inappropriate, declined or not tolerated will still receive some worthwhile benefit from the drug treatments if these lower blood pressure.

3 Besides blood pressure, what other advice and treatment does this patient require to ensure his risk of a cardiovascular event is reduced? Give clear reasons for your advice and explain the risks associated with not taking this advice.

This patient should receive appropriate advice on a range of lifestyle measures that may reduce his overall cardiovascular disease risk. In particular he needs to be encouraged to lose weight, stop smoking and to reduce his alcohol intake to within recommended limits.

The Clinical Knowledge Summary on Hypertension (2007) suggests that people with hypertension should be advised on appropriate lifestyle modifications to reduce cardiovascular disease risk. Advice should be given on:

- alcohol consumption

- diet

- physical activity

- smoking cessation

- weight reduction.

[/column]

There is evidence that a healthy diet, regular exercise and moderation of alcohol intake can reduce, delay or remove the need for long-term antihypertensive drug treatment (North of England Hypertension Guideline Development Group, 2006).

Combining dietary and exercise interventions reduces blood pressure by at least 10 mmHg in about a quarter of people with hypertension (North of England Hypertension Guideline Development Group, 2006). Detailed dietary, exercise and weight-loss advice is given in the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) eating plan (available from www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/hbp/dash).

Individual lifestyle modifications that are known to reduce blood pressure include (North of England Hypertension Guideline Development Group, 2006):

i. Regular aerobic exercise for 30–60 minutes, three to five times each week

ii. Moderating alcohol intake to recommended levels (less than 21 units per week for men; and less than 14 units per week for women)

iii. Restriction of dietary sodium salt to less than 6 g per day by reducing intake or substitution with low-sodium salt alternative

iv. Weight reduction in people who are overweight (body mass index [BMI] over 25 kg/m2)

v. Restricting coffee consumption (and other caffeine-rich drinks) to fewer than five cups per day

vi. Relaxation therapies (e.g. stress management, meditation, cognitive therapies, muscle relaxation, biofeedback) – can reduce the blood pressure, and individuals might wish to pursue these as part of their treatment (though routine provision by primary care teams is neither widely available nor currently recommended).

Weight reduction

Up to 30% of all coronary heart disease deaths have been attributed to unhealthy diets. In 1980, 8% of women were obese and 6% of men. By 1998, however, the prevalence had almost trebled to 21% of women and 17% of men. The four most common problems linked to obesity are heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension and osteoarthritis (National Audit Office, 2001). Healthy, low-calorie diets had a modest effect on blood pressure in over weight individuals with raised blood pressure, reducing systolic and diastolic blood pressure on average by about 5–6 mmHg in trials. However, there is variation in the reduction in blood pressure achieved in trials and it is unclear why. About 40% of patients were estimated to achieve a reduction in systolic blood pressure of 10 mmHg systolic or more in the short term, up to 1 year (NICE, 2006).

Reducing alcohol consumption

Excessive alcohol consumption (men >21 units/week; women >14 units/ week) is associated with raised blood pressure and poorer cardiovascular and hepatic outcomes. Structured interventions to reduce alcohol consumption can reduce on average SBP and DBP by 3–4 mmHg in clinical trials.

Smoking cessation

There is no strong link between smoking and blood pressure. But the evidence of the link between smoking and cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases is overwhelming. In addition there is evidence that smoking cessation strategies are cost-effective (NICE, 2006).

4 What are the main classes of drug used to treat hypertension?

Thaizide diuretics, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers and angiotensin II receptor blockers.

5 Which class of drug would be appropriate first-line treatment for Mr HA? How would this treatment choice be affected if the patient had been of Afro Caribbean origin?

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) would be the appropriate initial choice in this patient. If the patient had been of Afro Caribbean origin then a thiazide diuretic or calcium channel blocker would be an appropriate choice.

6 For one of the classes of drugs mentioned in question 4 indicate the following:

i. a drug from that class

ii. a suitable starting dose and frequency

iii. the maximum dose for hypertension

iv. three contraindications

v. three common side-effects.

Suitable starting doses, frequencies and maximum doses for some appropriate drugs are listed in Table A2.2.

Table A2.2 Suitable starting doses, frequencies and maximum doses for some appropriate drugs for Mr HA (hypertension)[end_columns]

| Drug | Dose | Frequency | Maximum dose |

| Ramipril | 1.25 mg | Once daily, increased at intervals of 1–2 weeks |

10 mg once daily |

| Lisinopril | 10 mg | Daily | 40 mg daily |

| Enalapril | 5 mg | Once daily | 40 mg once daily |

| Perindopril | 4 mg | Daily | 8 mg daily |

[column]Three contraindications are: (a) patients with a hypersensitivity to ACE inhibitors (including angioedema), (b) patients with known or suspected reno vascular disease, and (c) pregnancy.

Three common side-effects are: (a) first-dose hypotension, (b) persistent dry cough and (c) hyperkalaemia. Other side-effects include: gastrointestinal effects (nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, diarrhoea, altered liver function tests, blood disorders, angioedema, rash, loss of sense of smell (more likely if also on potassium-sparing agents or potassium supplements).

7 In view of Mr HA’s age he requires cardiovascular risk assessment. How would you assess this patient’s cardiovascular risks?

According to the Joint British Societies Guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in clinical practice (British Cardiac Society et al., 2005) the following patients should be assessed:[/column]

i. Adults >40 years with no history of CVD or diabetes who are not already on treatment for blood pressure or lipids should be opportunistically reviewed.

ii. Patients <40 years with a family history of premature atherosclerotic disease should also have their cardiovascular risk assessed.

Cardiovascular risk over 10 years >20% is high risk and patients should be targeted for advice to reduce this risk (i.e. blood pressure reduction, aspirin, dietary modification and drug treatment for modification of lipids, stop smoking, etc.).

In order to calculate cardiovascular risk for a primary prevention patient such as Mr HA, use a validted risk calculator. These are JBS CVD Risk Predictor Charts (Heart, 2005, 91: 1–52); BNF Extra (contains JBS CVD risk prediction programme. Available at http://www.bnf.org/bnf/extra/current/450024.htm); QRISK (Available at http://www.qrisk.org/).[end_columns]

General references

- Joint Formulary Committee (2008) British National Formulary 55. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, March.

- National Prescribing Centre (NPC) (2002) MeReC Briefing – Lifestyle measures to reduce cardiovascular risk. Available at http://www.npc.co.uk/MeReC_Briefings/2002/ briefing_no_19.pdf [Accessed 3 July 2008].

Author: Narinder Bhalla; BSc (Hons), MSc, MRPharmS. Pharmacist,Cambridge University Hospital.

How to read all case studies for asthama and case study for heart failure….