[column]Advances in genetic profiling have allowed doctors to match more of their cancer patients with treatments that will target their particular illnesses. But for some about one-third of cancer patients, there are no good matches, leaving them with only conventional chemotherapies and radiation.

Now Dr. Keith T. Flaherty, an oncologist, and his colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital have developed a more sophisticated formula for analyzing tumors to find their vulnerabilities.

On Monday, the hospital will unveil a partnership with AstraZeneca to pair Flaherty’s computer analysis with the company’s growing library of drugs to identify combinations of treatments that would not otherwise have been considered.

“Ultimately it is about going after a proportion of patients who in the current state of the art are unlikely to be matched with any targeted therapy,” said Antoine Yver, head of Oncology Global Medicines Development at AstraZeneca.

Although pharmaceutical companies such as AstraZeneca are bringing an increasing number of new cancer drugs to market, they don’t necessarily know — or have the tools to find out — which patients would be a good match for their treatments.

And finding more precise matches between tumor and treatment is crucial for ensuring that the drugs, most of which have damaging side effects, are also effective.

So, the collaboration between MGH and AstraZeneca is “very exciting and in keeping with a larger trend of targeting the right drugs based on a better molecular understanding of the patient’s genetics and the physiology of the particular tumor,” said Edward Abrahams, president of the Personalized Medicine Coalition, an education and advocacy organization that is based in Washington.

“At the end of the day, what we want to do is move away from one-size-fits-all medicine,” he said.

Massachusetts General Hospital routinely conducts a genetic analysis of all of its patients’ tumors, as do a growing number of hospitals around the country.

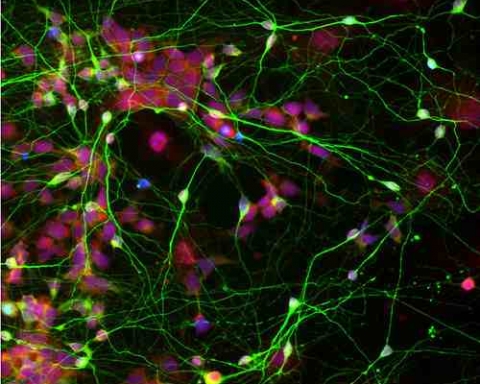

Knowing the genes that are turned on and off in a tumor can help doctors spot and target the tumor’s vulnerabilities. Some genetically targeted drugs, like Herceptin and Gleevec, have transformed the way some cancers are treated and dramatically extended patients’ lifespans.

Doctors are also realizing that one drug is usually not enough.[/column]

Tumors change over time, and, just as AIDS is now effectively treated with combination therapy, so cancers are increasingly treated with multiple drugs that attack in different ways to prevent them from spreading.

But many patients’ tumors aren’t an obvious match with known drug treatments.

For them, the process of finding an effective drug gets complicated quickly, Flaherty said.

There are about 60,000 genes in every cell, and different paths the cancer took to get launched, different proteins that might be created in the tumor, and so on. Flaherty and his team at Mass. General’s Termeer Center for Targeted Therapy have developed a formula for making sense out of this complexity and predicting the most effective ways to attack the cancer.

That will allow Flaherty to, for example, look for a drug that can attack a specific protein or another that reverses a certain pathway the cancer used.

Enter AstraZeneca.

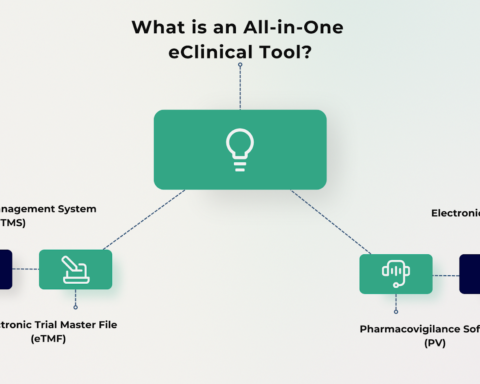

From developing cancer treatments for more than three decades, AstraZeneca has amassed a huge library of drugs, including chemotherapies, hormone therapies, and drugs that act on the immune system.

Since most patients will require a combination of therapies, Flaherty’s system can comb through AstraZeneca’s library to find pairings of drugs and treatments that previously had not been considered, Yver said.

Each new combination will require approval from the Food and Drug Administration, but Yver said he expects that to be a fairly painless process, since the drugs individually have already been tested and their appropriate doses determined.

However, the cancer patients who get matched up with a treatment by this collaboration will be guinea pigs, in a sense — the first to take their particular combination of drugs for their precise type of cancer.

Because of this increased risk, the approach will be tried first in patients with late-stage cancer whose tumors have already evaded other treatment.

Eventually, Flaherty said, he hopes to be able to use it in people with early-stage cancers in whom treatments are likely to be most effective.

Source: Written by Karen Weintraub on BostonGlobe.com. [end_columns]