Bioanalytics is defined as the analysis of a desired analyte in any biological fluids such as blood, plasma, serum, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid etc. Bioanalytical methods are therefore methods used to analyse an analyte in biological matrices. These methods are employed during the later stages of the drug development process (clinical trials) where the quantitative information about the drug after it has been administered inside a human body, is collected.

For long, bioanalytical methods have been playing a crucial role in analysing such samples and are helping to generate data for pharmacokinetic, bioavailability, drug-drug interaction, bioequivalence, and compatibility studies. Like analytical methods for the final drug, bioanalytical methods are also required to be validated for their intended use for the analysis of the compound of interest (e.g. this can be the future drug substance, but also metabolites). The importance of validation can never be overestimated as any mistake in the methods may prove to be lethal to human lives.

Recap and recent updates

Unlike the validation of analytical methods for drugs (drug substances and / or drug products), bioanalytical method validation is not yet harmonised. This means that although the regulatory bodies of different countries have a general agreement on the validation front, they are still to come to an agreement where there is one standard to be followed for the validation of bioanalytical methods.

Because of this, there exist many variations among the general requirements for validating a bioanalytical method and hence produces hurdles in generating reliable bioanalytical data for global drug development processes. Historically, in the 1990 conference for „Analytical Methods Validation: Bioavailability, Bioequivalence and Pharmacokinetic Studies” in Washington, for the first time, a consensus was reached on the validation parameters required for bioanalytical methods. Although it was a big step towards the development process, many key ingredients such as guidance on experimental designs and statistical evaluations were missing.

Fast forwarding, National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) for Brazil amended their own guideline in 2003 (RDC 899/2003), which was revised in 2012 as RDC 27/2012. The European Medicine Agency (EMA) for European countries, also made its guideline effective from 2012, and the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW) for Japan issued their guidance in 2013 and another one dealing exclusively with ligand binding assays in 2014. Having previously been the first one in 2001, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the United States of America have very recently (in May 2018) updated their previous guidance (the old official one of 2001, and the draft of the current one published in 2013) as a recommendation to the industries for validating bioanalytical methods. A chronological overview is presented in Figure 1.

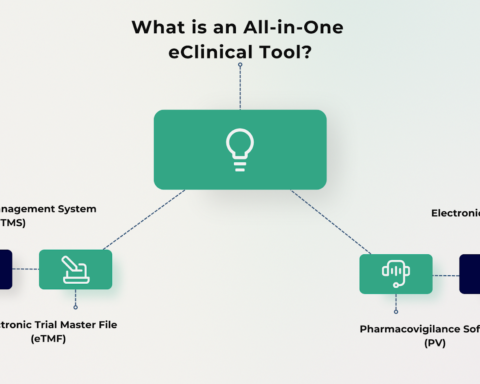

Amidst clear differences in the acceptance criteria that exist among these guidelines, there is at least an agreement on the general validation parameters that needs to be evaluated for bioanalytical methods. These include selectivity, calibration model, stability, accuracy (bias), precision, and limit of quantitation. Other parameters that may be required to be answered are limit of detection, recovery, reproducibility, and robustness (Figure 2).

Requirements

All the above mentioned guidelines are rather related to Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) instead of Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) as in the case of validation of analytical methods which are always associated with a drug that is to be launched soon. For bioanalytical methods, a full validation (covering all the validation parameters mentioned earlier) is recommended by all the authorities when analysing a new product and when a method is used for the very first time.

In case of any minor changes made to an existing method, the maintenance of the performance of the bioanalytical method can be shown by a partial validation (covering only some selected parameters depending on the change). A partial validation is suggested during a method transfer procedure, a change in equipment, a modification in calibration range, a change in sample processing protocol, and after modification in matrix components. There may be many other instances that may occur. These may be duly notified and if required, a partial validation must be performed to demonstrate the reliability of the method performance.

If two or more bioanalytical methods are used to generate data within the same study or across different studies, a cross validation might be necessary. The amount of parameters to be checked can vary from just a few selected ones depending on the method as to all of them just like in a full validation. Cross validations can help assessing inter-method equivalency or judging inter-laboratory implementation of the same method.

Figure 3 illustrates the underlying differences for choosing the validation type.

As mentioned earlier, the requirements reading the experimental design and the acceptance criteria for each parameter do strongly vary between the guidelines, as illustrated by the following example. For recovery in a chromatographic method, the new FDA guideline doesn’t define any acceptance criteria, while in the ANVISA guideline a 100% recovery is desired.

Future perspective

The good news, however, is that, the process of harmonization for bioanalytical method has already started. The International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) has issued a concept paper in October 2016 thereby acknowledging the need for this harmonization, which will be realized by the new M10 guideline and laying out a plan, defining Q2 2019 as key milestone to reach step 4. Compared to the tripartite nature of the ICH Q2(R1) for analytical methods, harmonization of bioanalytical methods will possibly have more participants. It is now very well understood and accepted that a harmonised bioanalytical method validation is the need of the hour to influence rational, economic, and effective clinical and non-clinical studies and the recent release of the updated US FDA guideline may well provide the boost required towards achieving this feat. Whether the ICH will adhere to the new US FDA guideline or will bring some significant changes remains a matter to be seen. Until then, we just have to be waiting by keeping our excitements down!

About Author

Dr. Janet Thode is CEO and senior consultant of Loesungsfabrik whose MPL division is a Pharma consulting firm in Germany, specialized in analytical quality control. With more than 8 years of practical laboratory experience (among others in a French CRO), she is always interested in finding realizable solutions in the fields of international method transfer, analytical method validation and filter validation topics. Working with global acting pharmaceutical companies in complex projects, she focusses on a good communication. She can be reached at: dr.thode@loesungsfabrik.de

This article is exclusive to pharma mirror readers only, do not copy!